Willingness to Pay for News

The news consumer had to be invented. The news consumer got that news for cheap.

In my Introduction to Media Studies class, we cover the history of newspapers in the US. A key turning point that the textbook offers is the move from the “party press” of the colonial era to the “penny press” of the 1830s or so, with Charles Dana and the invention of local news, sensationalism, and most importantly, a newspaper that only cost a penny - an amount most people could afford, compared to the 6 cent papers of party elitists.

This is generally presented as a big deal moment for American history - a nation stitched together by mass circulation newspapers. But this isn’t the most important part of the story for people who care about the financial sustainability of the news.

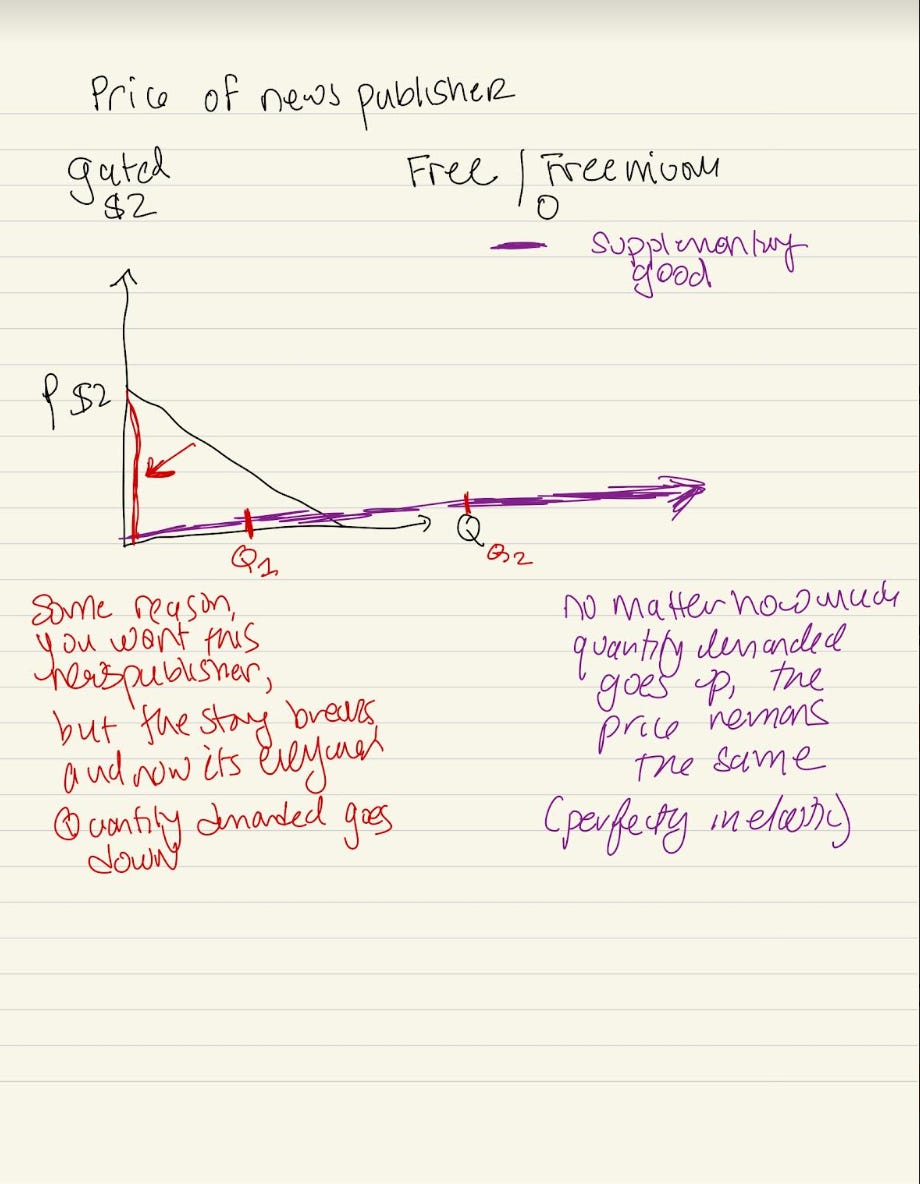

Rather, there are two important takeaways: 1) that a mass of people were willing to pay at all for news (that sometimes they couldn’t even read or understand!) and 2) that the penny papers did not raise prices as demand for news rose. Prices were frozen at 1 cent (adjusting here and there for inflation) - they were perfectly inelastic - that is, the quantity demanded had no effect on the price consumers paid for news.

This is quite at odds with any good you might think of - and the idea that as prices go up, quantity demanded goes down, and as prices go down, the quantity demanded goes up —it just never had a chance in journalism.

In this post, I rethink willingness to pay for news within a larger historical context and apply the multi-level analysis we used in the previous post to provide better insights about why it is so challenging to price news for anything other than free.

As the post got long, I turn in the next post to what we don’t know: generally what the quantity of news is — and why that matters to pricing the news.

Part I: Willingness-to-Pay for News: Reimagined

The heart of one of the most basic questions facing a firm in economics is what price to set for whatever it is they are selling. Ideally, the firm will set a price that consumers are willing to pay, covers the cost of making the good, and brings in the most profit possible.

Willingness to pay is a benchmark - willing to pay up to and including a certain amount, but no more. The consumer wins when the price of something is less than they were willing to pay; above the willingness to pay that the consumer has set for themselves, the good simply isn’t bought, quantity demanded goes down, and revenue plummets.

News industry observers often point to a problem with news - that no one wants to pay for news — well, ok, 26% of Americans say they have ever paid for news (ever) - I’ve seen as low as 14%. If people will not pay for news directly, and advertising dollars are gobbled by tech, then how on earth are for-profit commercial news organizations surviving? (answer: they aren’t, unless they are unabashedly partisan, but come back for more on that).

The reasons that we typically hear about why people don’t want to pay for news is that people got used to news being free on the internet and that news is an information good, so it just doesn’t have the same characteristics in the marketplace as your typical product — or even a service. Both of these explanations fail to account for the news industry’s basic failure to understand how to price goods. The missing gaps also make it even harder to account for the economic challenges that face commercial news organizations in an era of digital intermediaries (Facebook, Apple News, TikTok), cord-cutting, and fragmented, niche audiences.

Here’s the rub: The mass news consumer had to be invented. The American news consumer was habituated from early in American history that news should be cheap. A news buying public had to be created and the cost had to be low enough for them to take the risk that they might not like the content or find it useful at all.

Charles Dana, Joseph Pulitzer, and Hearst didn’t raise the prices for news, just the prices for advertisers, a concern that the regular news consumer wouldn’t be thinking about. Usually when price is inelastic it is because the good is a necessity: think an epi pen or insulin - people are still going to need the drug, and this need won’t change because the prices go up. Theoretically, people are willing to pay almost anything to have access to a drug that could save their lives.

The need for news became a way to leverage how much people were willing to pay for it: the more interesting and salacious the news, the larger the number of people willing to surrender a single cent. Heck, people could buy two newspapers, or the same newspaper in the morning and evening. The cost simply didn’t set them back. But generally, news doesn’t save lives, information may be a necessity, but a lot of news is a luxury (see Harry Backlund’s piece on this).

Television and radio did not help set expectations for a more significant willingness-to-pay to emerge as technology changed. Unlike newspapers, television and radio were FREE. So long as you paid your electric bill, you got free over -the-airwaves sound and visuals and top notch entertainment (although batteries could make a portable radio go). In fact, the logic of the FCC’s existence is that it serves a steward of the public airwaves, helping regulate what for most of the electronic age was a scarce resource—the frequencies on the electromagnetic spectrum— until we figured out how to maximize and expand it.

Rarely do we have a condition where a good was price inelastic but remained extremely low cost for the consumer, regardless of demand. This just doesn’t make sense from the standpoint of classical economics. The price for news never kept pace with demand from the earliest days of mass market media.

Journalism is also a highly supplemental good. Because of how information works - once the information is out in the world, everyone knows it and the news no longer holds the same value (literally the news is cheaper the more people know about it). People in news care about scoops, people outside of news care about the information.

Most of the news is not so unique that it is available only in once place - so if I’m being asked to pay for news by one news organization, I can likely get the same story somewhere else for free. The willingness to pay for news is low because where I get news about an event in the world is highly supplemental. Once I get the news, wherever I get it from, I probably have satisfied my news need. (I’ve learned the score, I don’t care where the news came from). If I can get free news from one outlet, why should I pay for any one specific news outlet to access that same story with the same information elsewhere.

(TBD: I will also put in a little spreadsheet table that shows the various problems of thinking through this question on the story, news item, and outlet levels, but I’m publishing now because I need to feel done with something today!)

The news industry also deserves to shoulder some of the blame for creating an industry where news about an event in the world is generally interchangable across news outlets (or news outlets that purport to be providing objective, verified news content). The news industry is so isomorphic: a news outlet cannot handle being scooped and must write/produce its own story. Leaving community news aside for a moment, every news outlet in the US will carry somewhere on its website the jobs reports, fed mortgage rate moves, reports about the latest big event in the world - and often that content won’t just be duplicative, it will actually be the same content (e.g. the AP).

Unless there is some definitive brand value proposition from getting news that I can find somewhere else without paying, there is no reason that we should expect anyone generally to ever actually pony-up for news.

Part II. On advertising and information goods

But isn’t journalism an example of a dual-product market, so your analysis is off? Well, yes, journalism is an example of a dual-product market: Audiences pay for news, but these audiences are sold to advertisers, who then pay for the eyeballs. To draw audiences to news in mass audiences, the news had to be cheap for them to experience.

This model STILL works: digital intermediaries like Meta and TikTok sell advertisers our data (and our attention) - and these companies are able to harness our attention for retargeting by advertisers better than any mass circulation/mass media news outlet ever could.

A fallacy that is often perpetuated is that news was “given away” for free on the internet. This is not true. The earliest online news was accessed via paid portals like America Online and Prodigy - it was sort of like paying for cable to get to the news channel. I write about this next stage of online news in News for the Rich, White, and Blue, the free years between the late 90s and 2008 or so, when the news industry bet that they were going to be able to capture huge, mass audiences online just as they did huge mass audiences off line. But it turns out that people do not just want to read news online - and especially at the article level that most of us consume news, well, there is no *destination* outlet, if there is even a homepage at all.

The advertising model isn’t broken, news is just fundamentally not as interesting as all the other content on the internet, so there is no monopoly on attention anymore. The costs of not buying the news — or not even swiping on the news — well, it’s at the cost of not doing something more interesting online. People are not used to paying much for news, if at all, nor have they ever.

But isn’t news an information good? So even if we accept what you have to say about price-setting history for journalism, information goods are just different, right?

Most people who will encounter my Substack know that journalism is generally thought of as an information good - it’s not something that disappears or expires once someone uses it, but lives on.

Typical good: I eat an apple, you can’t have the apple I ate, and there is one less apple at the cafeteria for everyone else.

Information good: As per my textbook, “Information is costly to create but cheap (often costless) to reproduce.” What might these include? “a database, game cartridge, news article, piece of music, or piece of software.” Separately, information services might include “e-mail and instant messaging, electronic exchanges, financial services, and internet based transactions, gathering data on clients, and so forth” (p. 72)

Also important: information goods and services have high fixed costs buts low or negligible marginal costs. Pay attention here - this is where journalism starts to depart from email, financial services or game cartridges.

High fixed costs - sure, it costs a lot to pay journalists, to run servers, offices, etc. set up distribution strategies, sell ads, etc. I’m getting it probably wrong, but I recall that The Times estimated it cost about $1million a year to keep the Baghdad bureau open, and this was from when I was doing fieldwork - so that’s 2010 dollars. Would it be possible to calculate that back into The Times’ overall revenue? Maybe, but - point being, for the 60 stories, let’s say, that someone wrote about Iraq that year, it cost $1 million just to keep the office lights on. Yipes. Does not look great in terms of ROI for team journalism.

But then there’s this concept that information goods are also characterized by low marginal costs—which is how much more the TOTAL cost of production increases for producing just one more unit. This is where I think journalism departs from what I’ve outlined above.

By this theory, to produce one more story really doesn’t cost more than producing the news, generally. But wait a second: why do we keep firing journalists and cutting the news hole?

If it is true that the cost to produce one more story really doesn’t cost more than the total cost, firing a journalist to save money really shouldn’t do much to the bottom line of a news organization anyway. In other words, of the fixed costs of news, the employment of a journalist is really a rounding error.

Or maybe it is that one journalist is a higher marginal cost - that the ROI of staffing a journalist actually does not justify the increase to the total cost of production, even though you might have some more news.

Up to this point, we haven’t even talked about the QUANTITY of news produced by any one news organization. And that Q helps us set price, where R = revenue.

This we will take up in our next post, but I will close with this:

I am more convinced that journalism has just never worked the way that we think it ought to as a basic economic good in order to produce meaningful commercial profits by any stretch of capitalist logic. In fact, much of modern memory about high profit news, especially high profit newspapers (think the 1980s) - well - it’s the same sort of boomer false nostalgia that plagues many other institutions.

Rather, don’t think about news in the US from 1950 to present, think bigger - a simile might be Mike Davis’ understanding of the growth of California. Southern California, for the vast millennia of existence has been an arid desert that doesn’t support life well, but has for the past three hundred or so years had the right mix of climate and resources to support the great Golden State. His point was that the gig was over: California is a barren land of earthquakes, plagues, fire, and drought.

As per that logic, for much of the history of news, news publishers struggled to stay afloat, and there was a blip moment in the human history of news in the 1980s and 1990s when the economy roared and newspapers made lots of money (*roared but for the 1987 Black Monday/Savings and Loan Scandal). But the gig is up for news, and in fact, has really always been a bit of a gig/gambit to begin with.

Up next: Demand as folly