The Economics of Journalism Have NEVER Made Sense

Or, how I'm taking managerial economics and this is what I've learned

Wow, it’s a trip to be in an economics classroom. Thomas Carlyle called economics the “dismal science” — and while I knew the phrase, I didn’t realize that he had written it in a paper to justify reintroducing chattel slavery into the West Indies to restore productivity and better reflect the “natural” law of supply and demand.

This gives you a sense of where economics puts its value. Today the reasoning remains the same: productivity. No apologies. The ideology is on the surface and that ideology is “make money for the firm.” Collateral damage is collateral damage, so long as that damage doesn’t undermine the firm, and in turn undermine profits.

Since I’m not going to be taking the midterm in the managerial economics class I’m taking, it works out better for me to think through the concepts and the associated formulas I’ve learned in terms of journalism and via this Substack post. So stay tuned for a bit: I’ll first give you a sense of the moral compass (or lack thereof) that guides economics as is presented in a 1st year intro MBA class, then I’ll go through some of the concepts I’ve learned and explain why the issue with journalism as a commercial enterprise is way more complicated than “journalism is an information good.”

TLDR journalism as we understand it from a news industry-first perspective is simply not a “good” that works for almost any basic premise in economics.

(side note: HUGE shout-out to the kindness of the brill Dr. Amy Nguyen-Chyung for letting me be present for this class and really shining a star on what excellent pedagogy looks like!) - Also to be very clear, I’m resisting the sort of early broad-based way of talking about the discipline, not the field itself!)

I. Economics is all about the gain, but assumes that firms have visible, predictable intentions that work out well for society

One of my early favorite lines in the textbook was:

Pursuing the profit motive, they constantly strive to produce goods of higher quality at lower costs. By investing in research and development and pursuing technological innovation, they endeavor to create new and improved goods and services. In the large majority of cases, the economic actions of firms (spurred by the profit motive) promote social welfare as well: business production contributes to economic growth, provides widespread employment, and raises standards of living —Samuelson & Marks, Managerial Economics, p. 11

The lack of reflectivity is astounding.

For instance, the consumer surplus is the phrase used to reflect how much gain people from paying less than the max they were willing to pay. At scale, the value that people gain from this difference is called social value, but the way it is phrased in economics is from firm-first: for instance, Uber created social value for consumers because people pay less for a ride than they are willing to pay. Social value becomes a concept we can measure as more or less by a raw numerical monetary amount —not a value. The only value in social value is how much money someone saves “in theory.” Not, the world was a better place, so a company or person added social value. Was there more value monetarily than expected— that is the social value that matters.

From the perspective of thinking through how to value people and how to maximize profit, from the get-go, human labor is the most expendable because it’s the “easiest” to manipulate.

For example: if you are trying to understand how to calculate the optimal production for a firm, the easiest form of the equation is below, where quantity is a function of the labor and the capital required to produce something. Without any sort of value judgment, an economics textbook will say that it’s easier to change labor than it is to change the capital required to produce - because you can make labor cost less or make people work more or have more people working for less:

So basically, if you want to make more money, you’ve got to squeeze out what’s in your control, which isn’t going to be the cost of raw materials or your factory size, but the people who work for you.

This simply doesn’t square with how journalism thinks of itself - the social value journalism provides is knowledge, working toward a better society, entertainment, a space for public debate, etc. etc. - nothing that is truly monetizable but reflects actual social value. But let’s take a closer look at some of the core premises of economics that simply have not shaken out for journalism - even at a time when news organizations had a monopoly on eyeballs insofar as selling audiences to advertisers, and even at a time when newspapers reigned supreme.

II. Thinking about Demand: Basic Economic Concepts Make NO Sense for News

I’m so inspired by Ben Thompson from Stratechery, though I tend to read his posts when I go looking rather than on the regular. So it’s quite possible I’m just restating his logic, but I’m doing it my way so buckle in, friends!

OK, if you are vaguely cognizant about economics, you likely have heard of the “laws” of supply and demand with respect to price. As supply goes up, demand goes down, but there is an equilibrium point where the quantity demanded equals the supply available — or what quantity producers are willing to produce of a good for a certain price is equal to the demand that consumers have for that good. This is Adam Smith’s grand contribution from 1776 (arguably the real shot heard round the world: the end of mercantilism and the birth of pure market capital) - and the concepts have generally held true since then, or at least insofar as liberal democracies understand how capitalism ought to work.

But these are two intersecting curves with two different stories to tell - and isolating each curve matters for our analysis because the way that supply and demand work for journalism are not quite the same as they are for other goods - if you are reading this Substack you also probably are vaguely aware that journalism is an “information good” that makes it different from a regular good that one consumes and then - it’s gone (there are a limited number of candy corns on my desk, and you can’t have the one I just had. You have to go buy your own damn candy corns).

The observation I’ll start with is that our news business models conversation gets very muddied by a basic issue: levels of analysis. Are we talking about getting one person to pay for news? Are we talking one person paying for one product? Are we talking about one product (publisher) in relation to other, supplementary publishers? So so many questions. The questions around news economics are further muddied by the disconnect between how journalists tend to think about output and how actual goods in markets work and that people want.

Let’s look first at the law of demand for journalism. The law of demand makes very little sense in today’s universe as anything worth predicting at all. Let’s consider this from a variety of perspectives that all share this truth in common:

I’m not saying anything rocket science but it should be helpful to just explain why these premises which seem basic to anyone who follows the industry makes so little sense we go back up the chain to think about macro economics and micro economics more generally.

Consumer demand for news is highly, highly variable.

Consumer demand for news is also highly segmented.

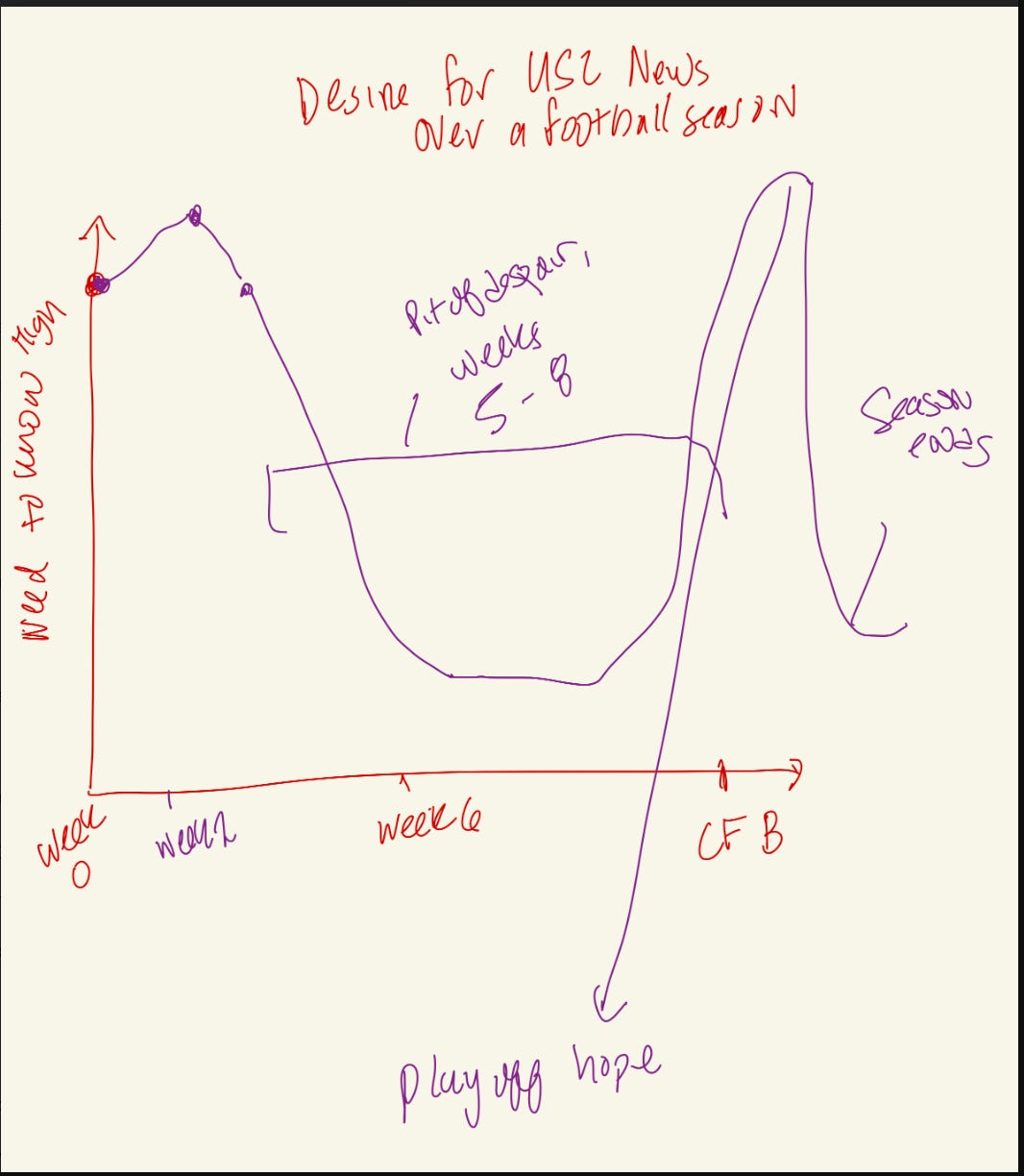

On any given day, the world might seem more or less worthy of orientation depending on what you care about. Let’s just take a simple news need - needing to know the score of a football game you didn’t watch. I don’t care about most of the stories from USC’s week leading up to the weekend game, although if I see some sort of alert about an injury, my demand to read about USC football midweek goes way up. But generally, I’ll wait until the weekend to check out what’s up with my team if I didn’t get to watch the game. Once I’ve gotten that news, I might be super depressed, angry, whatever - that anger might compel me to resign myself from ever caring about my team again and swear I will avoid watching college football - I’ll go into a spiral of college football news avoidance. But maybe I’ll be pissed off, and I’ll want to triage my sadness with news of another team’s sadness. Sometimes I’m motivated to spend more time reading about college football because I want to see that another team is ALSO doing badly, even if they are not in the Big 10 (still so weird to write for USC).

I’m just one consumer, but my need for news about college football depends on a whole host of factors. Even though there is an event in the world I know I care about every weekend for twelve weekends of Fall, my relative relationship to that particular event and how much I care is super volatile. It generally looks like this, although perhaps at scale, my behavior is not unlike many USC fans - but still, year over year, depending on the team, my attention patterns are likely to change.

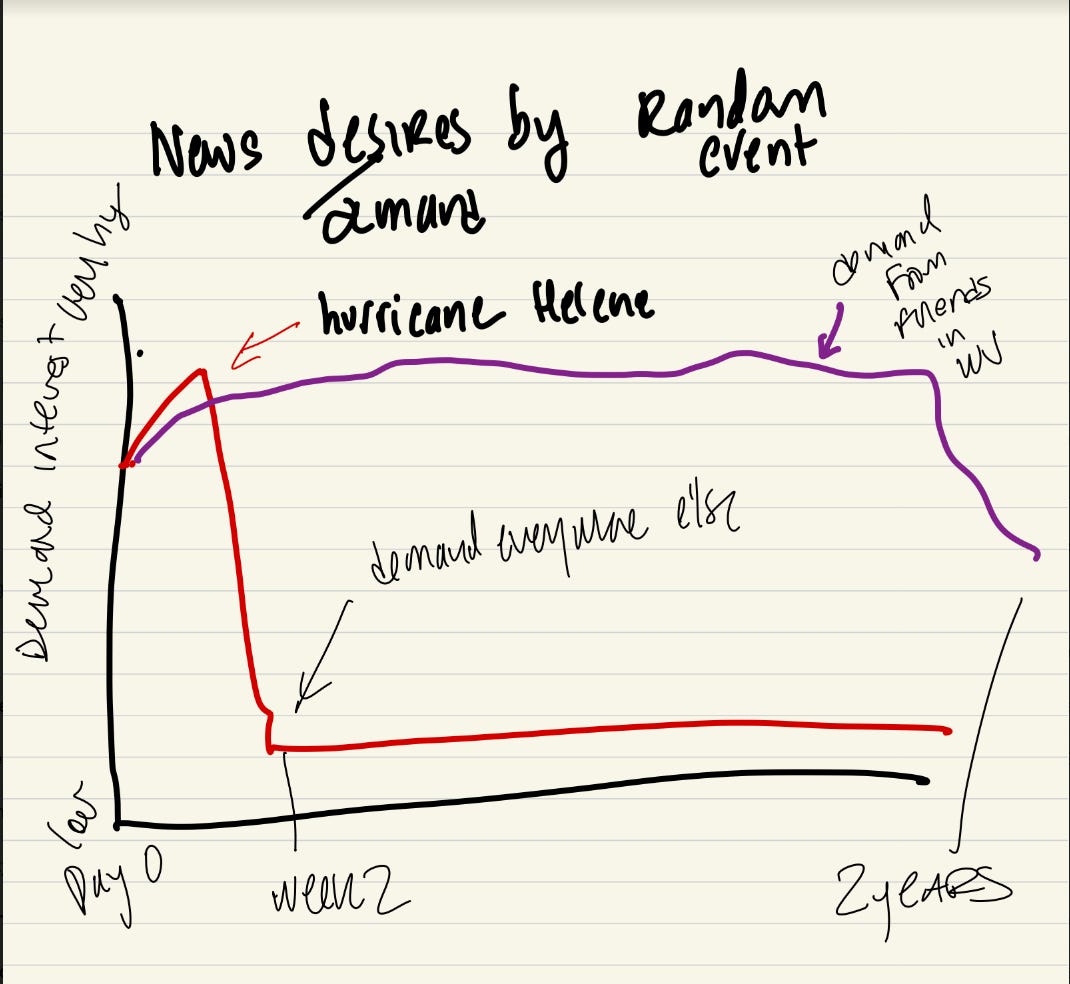

Now take this example of USC football and think about ALL THE NEWS ABOUT ALL THE THINGS IN THE WORLD. Some days, the whole world will want to know about an event, but where they learn about it from generally doesn’t matter. Add in the mix of the curation effect- some people won’t even see content they might actually like, especially if they consume news and information on a platform/digital intermediary. Even if everyone had the same news interests, which people definitely don’t, predicting that interest on any one day is downright impossible, which is why it’s so hard to definitely engineer a viral story.

Now, we can maybe budge demand a little bit - and maybe we can at least predict demand a little bit. But this really requires understanding just how segmented the news audience is.

There is a world of politics news avoiders who can tell you everything about T. Swift or last night’s red carpet or who is up and down at the Met Gala (many of these are my students). This is news, this is knowledge, and this is fundamentally political (the Met Gala has its first all-Black co-hosts ever), but it’s not P politics, I’ll buy the NYT every day. Actually, that sort of news reminds them what poor stewards of the world their parents have been…

To summarize this, I’ve also made it clear that there are real hard limits to demand. The attention economy is finite. News is just one tiny piece of the attention economy. And of that tiny piece, on any one day, being able to figure out how much demand there is requires predicting the future (which we can try to model, but realistically, the Mayans and economists are not so far apart in their successes on this) .

How we can predict demand: Well, these are the people that wake up every day wanting news, the people who pay for the product on the brand each week, regardless of what is in the news. These are the people who are junkies, but we can only predict demand most likely at the level of the news organization. It’s way harder to think about all the people that could be in our market and the variable demand they might have for news at any given day.

The core market for a news outlet is finite - as I’ve written about in News for the Rich, White, and Blue. Let’s just take a newspaper or television station, is finite, especially if it is a local news outlet - I’m not reading the Miami Herald regularly - I don’t live in Miami, don’t follow Miami sports teams, and have beaches close by to go see vs dream about. This core group is those folks willing to pay for news - who have regular new habits that include your outlet.

Do engagement efforts help? Our efforts at building engagement across new audiences - let’s say some awesome journalism trust effort intervenes in a community… the real sum total of people who might now decide to become part of that regular predictable demand maybe budges, at most, by 1,000 people? (thinking at the metropolitan scale).

As a reminder, trust in news really doesn’t have much to do with people’s willingness to pay for it, much less their desire to experience news each day. Is it true that people who are likely to trust the news are also more likely to pay for it — I think we think this to be the case, but there’s no magic equilibrium where if we can just push a city to 62% of residents trust the local television news, so the station can reliably charge X dollars for their attention — it just doesn’t work that way. Humans, thankfully, are variable, and how we spend our money and time is about as close as we get to freedom in this capitalistic universe. (And I’ve come to peace with this, for better or worse).

In the next post, I will talk more about about why understanding demand matters so much. And it matters because demand helps us set pricing and quantity. We’ll get to the problems with price AND quantity here…

If I got something wrong, please holler.

Also, if it isn’t entirely clear, I’m chafing against the barebones beginner economics - as my wife reminded me, social welfare, social value, etc. and economic redistribution can build efficiency and equity together, and thinking of my wonderful Barcelona School of Economics friends, that economists world-wide are trying to keep famines from starting, places from being flooded, trade deficits from growing, etc.